Gender based violence, education, and technocultures

Saint George School is an elite Catholic school in Santiago, Chile. At the end of May, news broke of an incident within the school where male students created AI-generated deepfakes of their female schoolmates to make them appear nude. The images went viral as they were spread both within and outside the school community.

This is a translation of an opinion piece published together with my advisor, Valentina Errázuriz Besa, in the newspaper El País

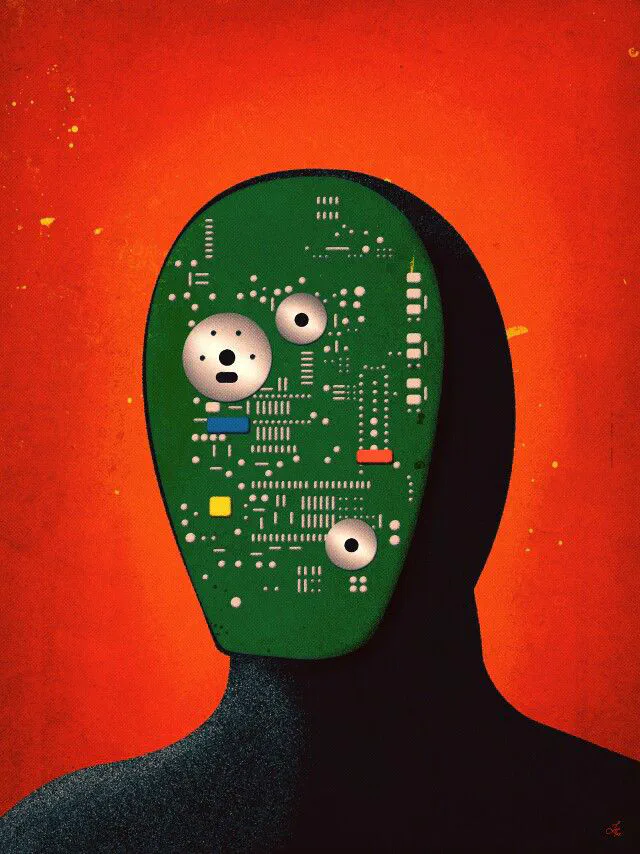

The recent case of students from Saint George School involved in generating and subsequently disseminating AI-modified images to make their classmates appear nude (a phenomenon known as deepfake) has sparked a series of debates. On the one hand, the necessity for legal definitions of acts involving the production of false images and information through technological means has been highlighted, as well as the importance of understanding what happened as an expression of gender-based violence. On the other hand, the role of schools in preventing malicious uses of technology and in digital literacy has been questioned.

We believe that any discussion on how to address the consequences of rapid technological development must be based on the understanding that technology is a sociotechnical product and, therefore, a cultural practice. This means that technologies are not autonomous elements independent of their contexts of production and use, while culture is also permeable to the possibilities offered by technology. In this way, society and technology shape each other and are not separate.

Following this premise, an analysis of what happened with the Saint George students must consider not only the evident sexual aggression and misogyny involved but also the technical elements that made it possible. The images in question were shared in a Telegram group with over 100 participants. The medium through which the event occurred is not irrelevant. Telegram is characterized by offering a sense of anonymity (only a phone number is required to register, and nicknames can be adopted) and facilitating the formation of closed communities that usually can only be accessed by invitation. These qualities of the platform can favor the normalization of gendered practices, specifically the reaffirmation of masculinity through the exercise of violence against feminized bodies.

This does not mean that the application is to blame for generating cultures of sexual aggression. Rather, it indicates that the technological context served, in this case, to proliferate already existing problems. Academic literature has coined the term toxic technocultures to refer to how the development of software—such as deepfake generators—entails processes of reproducing binary gender norms that are overlooked among developer communities. Particularly, since the content is artificially generated, it becomes easier to dehumanize those involved in the deepfake and to relativize the harm these technologies can cause. Thus, toxic technocultures depend on the combination of a specific cultural configuration and a platform.

Therefore, to devise educational strategies capable of addressing complex phenomena such as the intersection of technologies and oppressive cultures, it is not enough to ban technological artifacts or define exemplary punishments. It is necessary to analyze how the network of relationships involved leads to harmful sexist consequences and what other possible relationships could exist. In this regard, comprehensive sexual education (CSE) can educate towards the healthy consolidation of sexual-affective relationships and the prevention of gender-based violence. Moreover, since technology can be—but is not necessarily—an amplifying agent of sexism and gender-based violence, as well as other forms of injustice (racism, classism, ableism, ageism), it is also necessary to develop educational proposals around digital care. These proposals must consider that technological literacy is not a neutral skill, as it involves situating social practices in digital contexts with a view to constructing spaces based on greater well-being and less harm. Considering these points, it might be possible to dismantle the structures of oppression that permeate both the material and digital worlds.