Ruminations

I actually tried to post this before, but I haven’t been able to finish it until now.

It’s been almost five months since I passed my PhD candidacy exam. In the days immediately after, I wrote down some thoughts. What follows is a revisitation and reshaping of those notes from a different time, and consequently from a different point of view, or rather, standpoint. In that sense, this writing exercise in itself has become a data-production device of sorts (just like any other writing on this blog).

The process of preparing my candidacy proposal was intense. PhD programs often operate under the assumption that two years of doctoral practice is enough to move on to crafting a research proposal. There’s little room for contingency. If you can’t do it, then perhaps academia is not for you. After all, life is what happens when you’re busy doing your PhD, and academia, it seems, is what happens instead of life.

I exhausted myself to be strict on my PhD progression. I pushed hard to stay on track. I didn’t actually start working on my proposal until a few months before the two-year mark, so I had to pay my “debts” for it. I’d say I worked on it for three intense months. I did it at the expense of my health, though.

See, the way I think and write often requires my full and undivided attention. It makes me forget to eat. To stand up from the chair. It makes me forget to go to the bathroom. And I say it literally and not as some quirky academic anecdote. If I didn’t have my amazing partner, who’s also inside the loops of academic work, things would have been much harder. I managed to meet the expected deadlines, but only through a routine that was borderline self-harming.

So it’s no surprise I wasn’t able to engage in other academic writing things as much, like this very blog.

Much of academic life is driven by a dark desire to be able, of proving ourselves as able, to be validated, despite the harm. It’s an economy of being able, of rewarding over-performance and turning away from vulnerability. Every day I watch peers put their energy into proving their worth through the PhD, so they are deemed valid. I happen to be in an unusual position; I can sustain an all-consuming schedule without too much of a trouble, because I have few other responsibilities.

But I do have a disability. I’m autistic. I’m attention divergent. I live with chronic pain and rely on medication that partially helps with stiffness, and with some of my attention issues. It mostly works against me, because the kind of life rhythm required to pursue a PhD, and then, if lucky, survive in academia, is one structured around ableism. Academia tends to celebrate those who push themselves to the limit, who are willing to sacrifice their bodies to be blessed with a university position.

The naturalization of unhealthy ways of production is academia’s way of testing whether you are able enough to belong; it’s the ultimate being able test. Of who is able to prove great and constant productivity, who is able to hide their own pain, who won’t bitch too much.

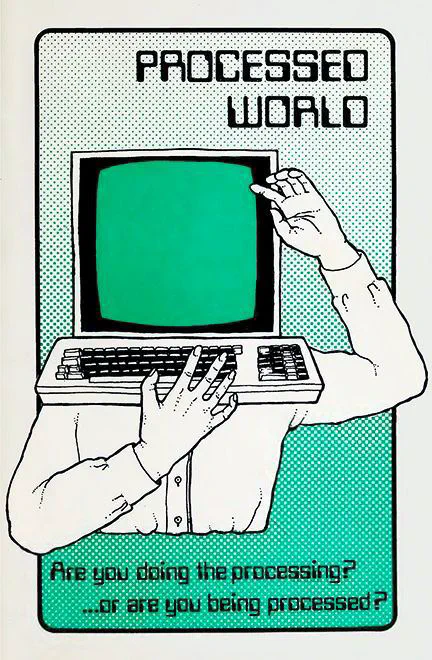

I’ve been thinking a lot about the PhD as a professional career path. Mostly about how it is that it gets to function like a machine, something I took from both Linda Henderson, Eileen Honan and Sarah Loch’s academicwritingmachine and Angelo Benozzo, Neil Carey, Michela Cozza, Constance Elmenhorst, Nikki Fairchild, Mirka Koro and Carol A. Taylor’s AcademicConferenceMachine.

Academia is composed of smaller machines that police the boundaries of who is deemed able and worthy enough to be part of it. It must do so if it wants to show itself as a structured, regulated space of legitimate knowledge production. Even if it means becoming overly regulating, overly normalizing, and overly standardizing.

And we want to belong.

As put by Nikki Fairchild, Carol A. Taylor, Angelo Benozzo, Neil Carey, Mirka Koro and Constance Elmenhorst: why are we seduced by the AcademicConferenceMachine? The purpose of the conference materializes multiple becomings linked to prestige and promotion, academic/non-academic labour, the fun of connecting and collaborating with friends.

As machines, both the AcademicConferenceMachine and the academicwritingmachine shape who we are as academics, and what we must accomplish to be recognized as legitimate. We crave legitimacy and recognition. We learn to navigate and willingly participate in a hyper-quantified and hyper-individualized datafied university through academic conferences and publications.

We can’t separate ourselves from these machines.

We are part of the machine.

Quoting Henderson, Honan & Loch: This academicwritingmachine is not something impacting on us academics, crushing us and wounding us. As academics within the neo-liberal university it is us making the movements.

I often think that is most likely impossible to bypass ableist barriers in academia. It’s a machine that rarely malfunctions at all, because it is designed and performed precisely so that it never ceases to be ableist. If it stopped being ableist, how it would validate itself? Whether through productivity metrics, surveillance, or any kind of datafication practice, ableism is the mechanism of validation.

The many machines of academia can be called academicXmachines. I use the term to name the multiple machinic assemblages that compose the academic ecology. There are as many academicXmachines as there are controlling dividuating forces in academic careers. I believe that if we map how academia functions, we might begin to get to understand how to disturb it.

Academia keeps the ball of a cognitive assemblage rolling. A cognitive assemblage thoroughly saturated with ableism. It’s a cognitive assemblage because its power lies in the mobilization of humans, non-humans, and datafication artifacts that shape what we come to understand as “academic”.

So, it’s not trivial that we need to find ways to try and interrupt the ongoing loops of the academicXmachine: we should reject strong humanist standpoints that lead to ableism and instead build affirmative, safer spaces for imagining kinder, more ethical ways of life. We must hold onto the hope that knowledge production can be oriented toward care, not toward self-inflicted or other-infliced pain, whether physical, psychological, or symbolic.

Instead of proposing a research project that conforms to the academicXmachine, I tried to make space for emergent ways, alternative knowing practices. If my proposal aims to be seen as post-qualitative research, the academicXmachines will inevitably demand that I justify its very existence. That it be “rigorous enough”, “scientific enough”, “worth it”. Fortunately, I was supported by a committee of generous academic women, Valentina Errázuriz, Ana Luisa Muñoz-García, Andrea Valdivia, and Juliana Raffghelli, who not only encouraged me, but were willing to stretch the margins of what is possible within this mode of making a living we call academia.

This doesn’t mean that the academicXmachine isn’t still gatekept. For an instance, preparing my ethics application was a deeply tedious task. I managed to do it in about ten hours of that no-eating, no-standing-up and no-bathroom time. It was tedious because I was cornered to a very conventional structure. I was compelled to represent things that I was trying not to represent at all. The academicXmachine worked by forcing my re-entry into the representational regimes my proposal seeks to resist.

The sociotechnical relations that comprise the academicXmachine force me to perform my worth, to stay able, to remain valid through performative complicity. Through a representational lens and conventional research language.

But again, I’m lucky. I wasn’t cornered in the crucial moment of my PhD candidacy exam, thanks to the lovely woman on my committee, who met me where I was, and welcomed my work. This post is also a way of thanking them for the profound insights they offered into this still-emerging project. Their support is now embedded in the cyber-body of this research assemblage. Having such a collective rooting for my work encourage me to keep experimenting and seeking to produce knowledge in different ways.

I’m excited to begin this journey of questioning how the postdigital is framing our modes of existence and conditions of possibility within academic work. I want to dive into the depths of the academicXmachine cognitive assemblage. The academicXmachine can no longer be thought apart from datafication and generative artificial intelligence. I’m deeply curious about how new cognoscent machines might help dismantle the academicXmachine.

But, as I said at the beginning, I haven’t been able to finally write about it… yet. I will soon, though. The AcademicConferenceMachine is hungry, and I need to feed it. I’ve already committed to a conference, so I’ll commit myself again. Just keeping the machine rolling till it tear us apart. And yet, I’ve witnessed the academicXmachine being disturbed. It can be disturbed.